By: Jude Chartier [AI Nurse Hub]

Introduction

The nursing shift of 2026 is faster, denser, and more data-rich than ever before. Despite promises that automation would ease the burden, cognitive overload remains a primary occupational hazard. In this high-pressure environment, a quiet phenomenon has taken root in breakrooms and nurses’ stations across the globe: “Shadow AI.” This term refers to the use of unsanctioned, general-purpose generative artificial intelligence tools—such as advanced large language models (LLMs) accessible via personal smartphones—by clinicians to perform their duties.

Drawn by the astonishing speed and seeming competence of these consumer tools, nurses are bypassing institutional IT protocols to summarize complex patient histories, interpret unfamiliar lab arrays, check drug compatibilities quickly, or even troubleshoot unfamiliar hospital equipment. While born from a desire for efficiency and improved patient care, this reliance on unapproved “shadow” tools creates significant ethical, legal, and clinical risks.

The central tension of nursing today is the gap between the immediate availability of powerful consumer AI and the slower, necessary pace of validated clinical implementation. Addressing this requires institutions to move beyond prohibition toward comprehensive education and the rapid adoption of safe, sanctioned alternatives.

The Lure of the Shortcut: Why Nurses Turn to Shadow AI

The driving force behind Shadow AI is not malice, but necessity. The modern electronic health record (EHR) is a repository of immense data, but it is often notoriously difficult to navigate quickly. A nurse facing a patient with a rare constellation of symptoms and a fifty-page history may find themselves tempted to copy non-identifiable segments into a commercial LLM, asking for a summary of comorbidities or a breakdown of a complex disease process they haven’t encountered since nursing school.

Similarly, while hospital databases exist for drug compatibility, they can be cumbersome compared to the conversational interface of a generative AI that can instantly synthesize information about multiple interacting medications. Furthermore, faced with increasingly complex biomedical devices, a nurse might find it faster to ask an AI how to calibrate a specific monitor than to hunt down a physical manual or navigate an outdated intranet. In the exact moments where institutional resources feel inadequate or too slow, Shadow AI offers an immediate, albeit risky, cognitive lifeline.

The Hidden Dangers: General-Purpose Models in a Clinical World

The fundamental danger of Shadow AI lies in a misunderstanding of the tool itself. The consumer-grade LLMs accessible on a smartphone in 2026 are linguistic marvels, trained on the entirety of the open internet. They are not, however, clinical decision support systems validated for healthcare.

The Hallucination Hazard

General-purpose models are designed to produce plausible-sounding text, not necessarily truthful text. In clinical scenarios, this tendency toward “hallucination”—confidently inventing facts—is catastrophic. A study evaluating the performance of general LLMs on medical inquiries found that while they could pass standardized medical exams, their real-world application was marred by subtle fabrications in complex scenarios involving multiple variables (Haupt & Marks, 2024). A nurse using such a tool to understand a complex procedure might receive an explanation that sounds authoritative but contains critical anatomical or procedural errors.

Bias and Health Equity

Furthermore, because general models are trained on internet data, they inherit the systemic biases present in that data. Research has consistently shown that standard algorithms can perpetuate racial and socioeconomic disparities in healthcare recommendations (Obermeyer et al., 2019). When a nurse uses an unapproved model to help understand clinical results, they risk viewing that patient through a lens of statistical bias rather than individualized assessment, potentially leading to under-triage or misinterpretation of symptoms for marginalized populations.

The Privacy Minefield

Perhaps the most immediate consequence involves patient privacy. Despite a nurse’s best intentions to de-identify data, pasting clinical vignettes into commercial AI platforms often violates the terms of service of the hospital and potentially HIPAA regulations. Once data is entered into many commercial models, it may be used to retrain that model, effectively releasing protected health information into the wild. The legal and professional liability in these instances falls squarely on the individual clinician.

The Imperative for AI Literacy in Nursing Education

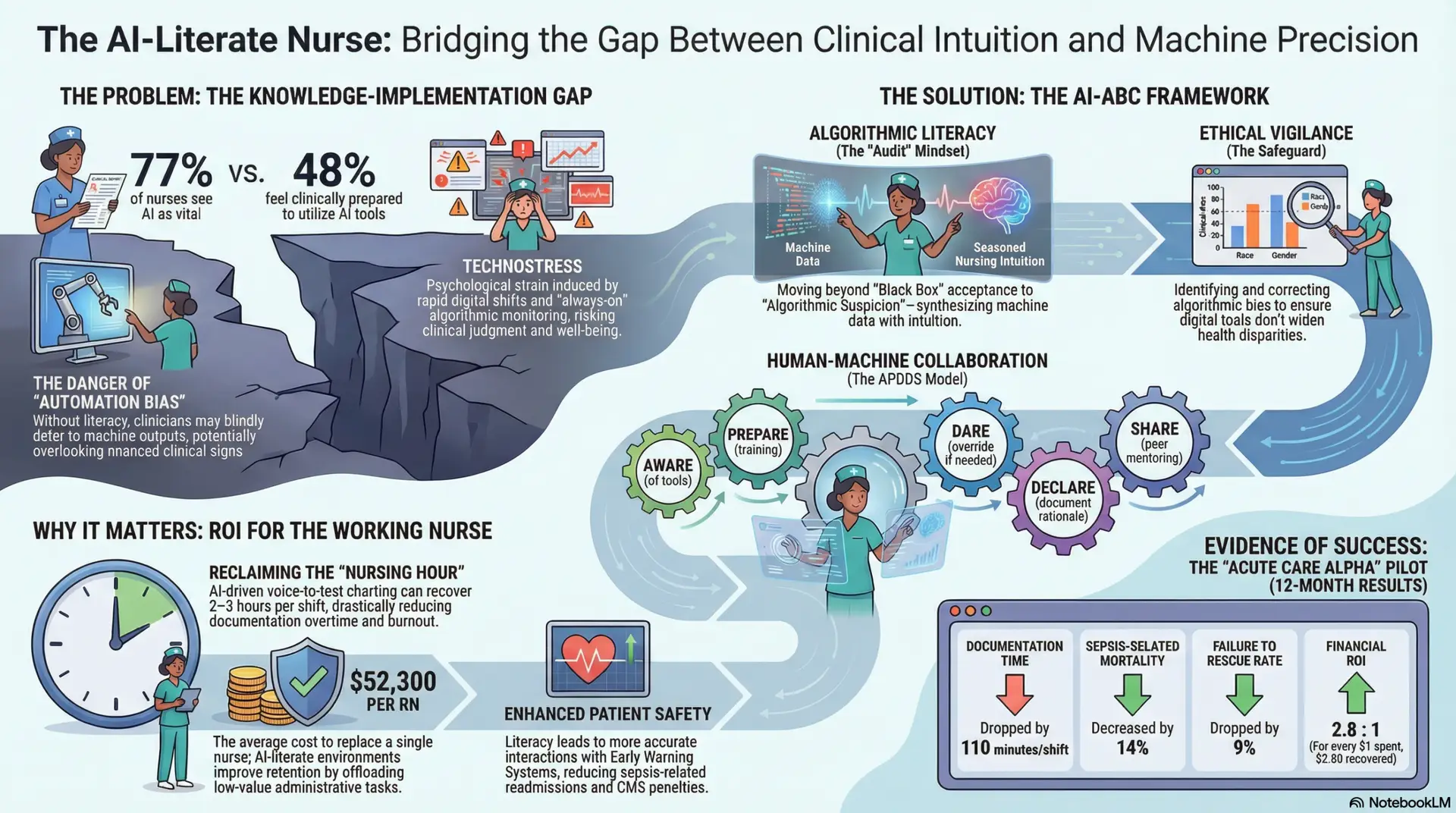

The existence of Shadow AI is a symptom of an educational and technological gap. Nursing demands a new competency: AI Literacy. This goes beyond knowing how to push buttons; it requires a critical understanding of how these models function, their limitations, and the ethical implications of their use in care settings.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) has emphasized that nurses must be leaders, not just users, in the integration of technology (ANA, 2025). Education must focus on “epistemological humility”—knowing what the AI does not know. Nurses need to be trained to treat AI output with the same skepticism they would apply to a new student’s assessment: interesting, potentially helpful, but requiring verification against validated sources and their own clinical judgment. Without this educational foundation, nurses are ill-equipped to distinguish between a helpful AI nudge and a dangerous AI hallucination.

Institutional Action: From Prohibition to Partnership

The current state of AI in healthcare institutions is fragmented. Some leading systems have fully integrated, HIPAA-compliant generative AI “sidebars” within their EHRs, providing nurses with safe tools for summarization and documentation. However, many institutions still rely on policy bans that are proving ineffective against the ubiquity of smartphones.

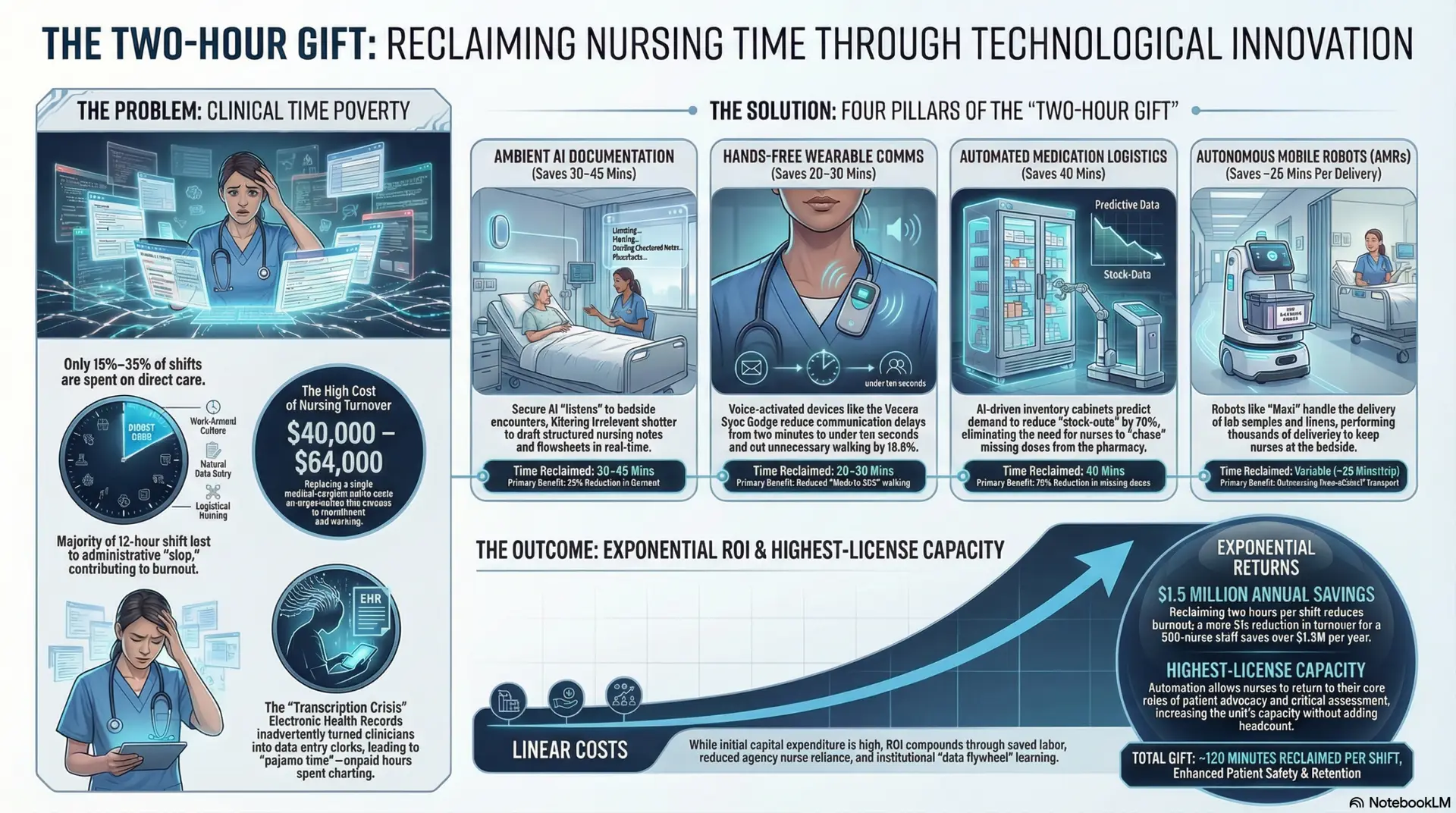

To rectify the risks of Shadow AI, institutions must take immediate, pragmatic steps:

- Acknowledge Reality and Pivot to Education: Blanket bans on generative AI are unenforceable and alienate staff. Instead, leadership should hold transparent town halls acknowledging the temptation of these tools while clearly articulating the specific clinical and legal risks.

- Create Safe “Sandbox” Environments: If the institution does not have an approved clinical AI, they should provide access to a secure, enterprise-grade version of a general model that does not train on inputs, allowing nurses to utilize the tools for non-patient-specific administrative tasks or general knowledge inquiries without risking data privacy.

- Accelerate Sanctioned Tools: The ultimate solution to Shadow AI is bringing better light. Hospitals must prioritize implementing validated, EHR-integrated clinical AI tools that solve the exact workflow bottlenecks that drive nurses to use their phones in the first place.

Conclusion

Shadow AI in nursing is a modern manifestation of an age-old nursing tradition: finding workarounds to get the job done for the patient in a broken system. However, the stakes of this specific workaround are untenably high. By relying on unapproved, general-purpose tools for clinical interpretation, nurses risk trading accuracy for speed, introducing bias and potential error into the care continuum. The path forward is not through punitive measures, but through rapid institutional adaptation, robust education, and providing nurses with the sanctioned, safe technological partners they deserve.

References

American Nurses Association (ANA). (2025). Position Statement on Artificial Intelligence in Nursing Practice: Ethical Integration and Human Oversight. Silver Spring, MD: ANA.

Haupt, C. E., & Marks, M. (2024). AI-Generated Medical Advice—GPT and Beyond. JAMA, 331(16), 1363–1364. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.2713

National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). (2024). The regulatory implications of unsanctioned artificial intelligence use in clinical settings. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 15(2), 14-22.

Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447-453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

Topol, E. J. (2025). As artificial intelligence goes multimodal, medical applications multiply. Nature Medicine, 31, 23–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02772-w