By: Jude Chartier [AI Nurse Hub]

Introduction

In the curriculum of nearly every nursing program, the “human touch” is presented as the quintessential, non-negotiable element of the profession. We have long argued that while artificial intelligence (AI) might master algorithms and diagnostics, it cannot replicate the tactile empathy, the delicate dexterity, or the sensory-rich interaction of a nurse’s hand. However, as we stand at the precipice of a new era in healthcare technology, this argument is rapidly losing its foundation.

Advancements in “Embodied AI”—intelligence that is physically housed in sophisticated robotic forms—are bridging the gap between machine and human sensation. With the development of haptic sensors, electronic skin (e-skin), and high-degree-of-freedom robotic hands, the technical milestones once thought to be decades away are now here. For the modern nurse, it is imperative to move beyond the comfort of the “human touch” defense and understand how these technologies are achieving, and in some cases surpassing, human tactile capabilities.

The Technical Milestone: Precision and Dexterity

The human hand possesses roughly 27 bones and over 30 muscles, allowing for “degrees of freedom” (DOF) that have historically been impossible to mimic. However, recent breakthroughs in robotic actuation have changed this landscape.

The Shadow Robot Company has developed a “Dexterous Hand” that mirrors the human hand’s 20 degrees of freedom and includes a “palm flex” feature that allows the thumb to oppose the little finger, a critical movement for grasping small objects (Shadow Robot Company, n.d.). Similarly, Sanctuary AI has unveiled its “Phoenix” robot, which features a hand system designed specifically for human-like manipulation. With over 20 degrees of freedom and proprietary haptic technology, these hands can now perform the “pill and needle” test—successfully grasping, orienting, and manipulating small medication vials, syringes, and individual tablets with precision that rivals a veteran nurse (Sanctuary AI, 2024).

In 2024, the National Science Foundation (NSF) awarded a $52 million grant to Northwestern University to lead the Human AugmentatioN via Dexterity (HAND) center. This initiative is specifically aimed at creating robots capable of “intelligent and versatile grasping” for healthcare and caregiving roles, addressing the exact fine-motor gaps that once separated nurses from machines (Northwestern Now, 2024).

Overcoming the Sensory Barrier: The Rise of E-Skin

The primary argument for the irreplaceability of the human touch has been our ability to feel. A nurse palpating an abdomen is not just applying pressure; they are sensing temperature, moisture, and tissue resistance.

The development of multisensory electronic skin (e-skin) has dismantled this barrier. Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin recently debuted a stretchable e-skin that maintains sensing accuracy even when deformed—a major hurdle in previous models. This skin allows a robot to sense pressure with a sensitivity higher than that of human finger pads, enabling tasks such as checking a patient’s pulse or performing a soft tissue massage without the risk of applying excessive force (Lu et al., 2024).

Furthermore, research published in Science Robotics (2025) describes a gelatine-based “intelligent skin” that can simultaneously detect pressure, temperature, and even “pain” (mechanical damage). This skin can detect forces as low as 0.01 Newtons—far more sensitive than the human threshold—allowing the AI to perceive the difference between a delicate vein and surrounding tissue during a difficult IV insertion (University of Cambridge, 2025).

Embodied AI and World Models

The true “brain” behind these hands is Embodied AI (EmAI). Unlike generative AI (such as ChatGPT), which operates on text, Embodied AI uses “World Models” to understand physical cause and effect. This means the AI isn’t just following a program; it is learning the physics of a patient’s room.

A 2025 survey in Healthcare Techniques and Applications notes that EmAI can now integrate multimodal data—visual, auditory, and tactile—to “plan” a physical interaction. For instance, if a patient’s skin is cool to the touch (detected by e-skin) and the AI sees the patient shivering (visual), it can autonomously decide to provide a warm blanket, executing the grasp with the appropriate pressure to avoid skin tears in elderly patients (Wang et al., 2025).

Relevance to the Nursing Profession

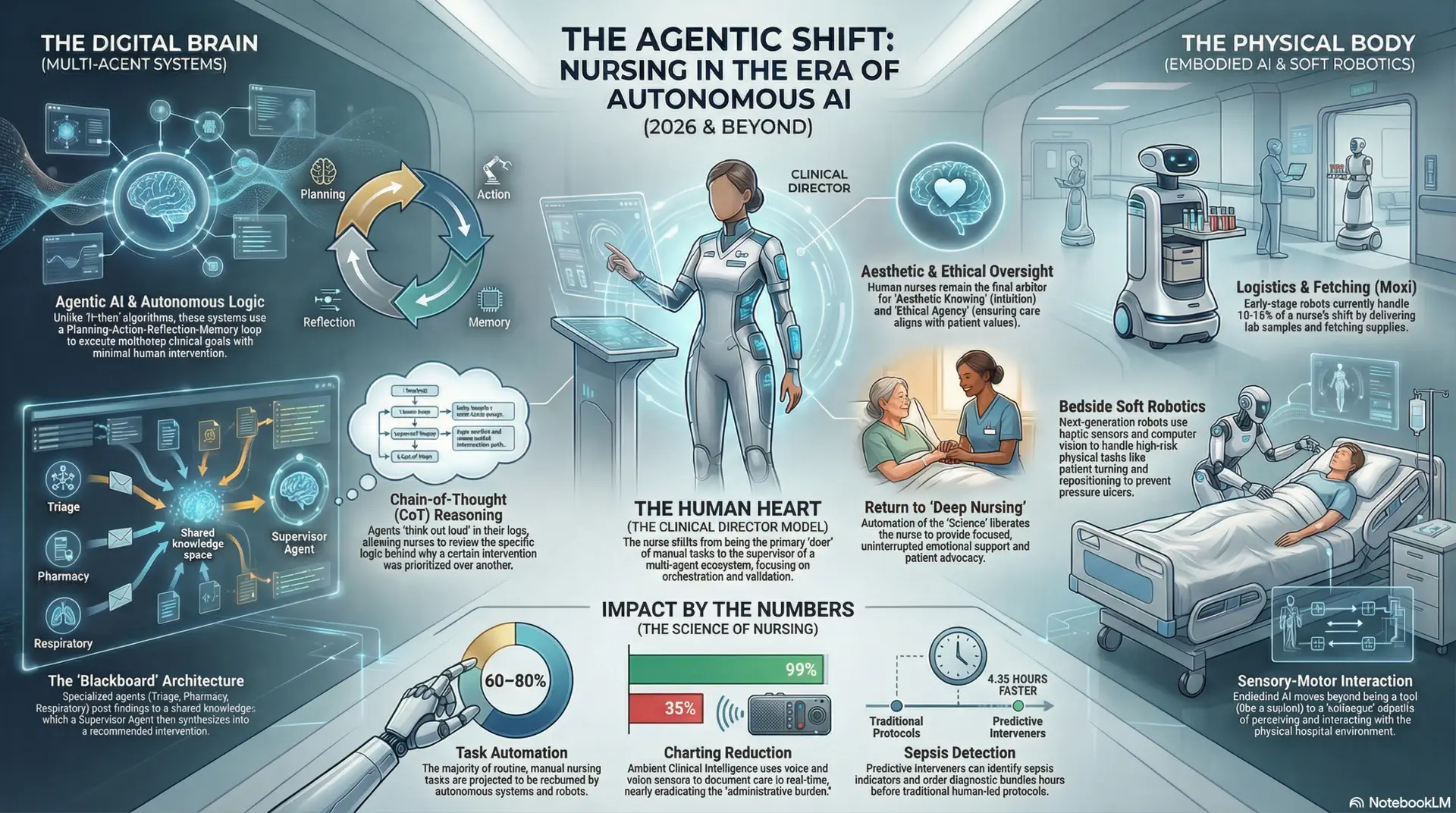

As these technologies transition from research labs to clinical settings, the role of the nurse will shift from the provider of the touch to the supervisor of the technology. We are seeing a move toward “collaborative robots” (cobots) that assist with the heavy tactile lifting—literally and figuratively.

Studies published in Frontiers in Robotics and AI (2024) indicate that nurses’ perceptions of these technologies are becoming increasingly favorable as they realize the potential for robots to offload physically demanding or high-precision tasks, such as drawing up micro-doses of medication or managing toileting for immobile patients (Babalola et al., 2024).

Conclusion

For years, we have used the “human touch” as a psychological safety net to protect our profession from the threat of automation. However, the milestones of dexterity, thermal perception, and pressure sensitivity have been met. With robotic hands that can feel a pulse, manipulate a needle, and sense the warmth of a feverish brow, the distinction between “human” and “robotic” touch is becoming a matter of semantics rather than capability.

As nurse, our goal is no longer to compete with machines in dexterity, but how to lead the integration of these embodied AI systems. The future of nursing is not in the hands themselves, but in the wisdom of the human who directs them.

References

Babalola, G. T., Gaston, J. M., Trombetta, J., & Tulk Jesso, S. (2024). A systematic review of collaborative robots for nurses: Where are we now, and where is the evidence? Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2024.1398140

Lu, N., et al. (2024, May 2). Stretchable e-skin could give robots human-level touch sensitivity. UT Austin News. https://news.utexas.edu/2024/05/02/stretchable-e-skin-could-give-robots-human-level-touch-sensitivity/

Northwestern Now. (2024, August 21). New center to improve robot dexterity selected to receive up to $52 million. https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2024/august/new-center-to-improve-robot-dexterity-selected-to-receive-up-to-52-million

Sanctuary AI. (2024). Sanctuary AI equips general purpose robots with new touch sensors for performing highly dexterous tasks. https://www.sanctuary.ai/blog/sanctuary-ai-equips-general-purpose-robots

Shadow Robot Company. (n.d.). Shadow dexterous hand series. https://www.shadowrobot.com/dexterous-hand-series/

University of Cambridge. (2025, June 16). Robots that feel heat, pain, and pressure? This new “skin” makes it possible. ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/06/250616040237.htm

Wang, B., Chen, S., & Xiao, G. (2025). A survey of embodied AI in healthcare: Techniques, applications, and opportunities. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/html/2501.07468v1