Date: January 15, 2026

By: Jude Chartier / [AI Nurse Hub]

Abstract

The global healthcare landscape is currently facing a dual crisis: a critical shortage of nursing professionals and a rising prevalence of chronic wounds, particularly diabetic foot ulcers and pressure sores. While artificial intelligence (AI) has made significant strides in diagnostic imaging, the physical act of wound care remains a manual, labor-intensive task. This article examines the transition from specialized surgical tools to fully autonomous, embodied AI robots capable of routine wound management. By analyzing current technological barriers—including haptic sensitivity, multi-modal computer vision, unstructured environment navigation, and sterility—this roadmap demonstrates how emerging solutions in soft robotics and edge computing are making autonomous care possible. Ultimately, this technology is positioned not as a replacement for human clinicians, but as a sophisticated clinical adjunct that allows nurses to focus on complex patient advocacy and strategic health management.

I. Introduction: The Premise of Possibility

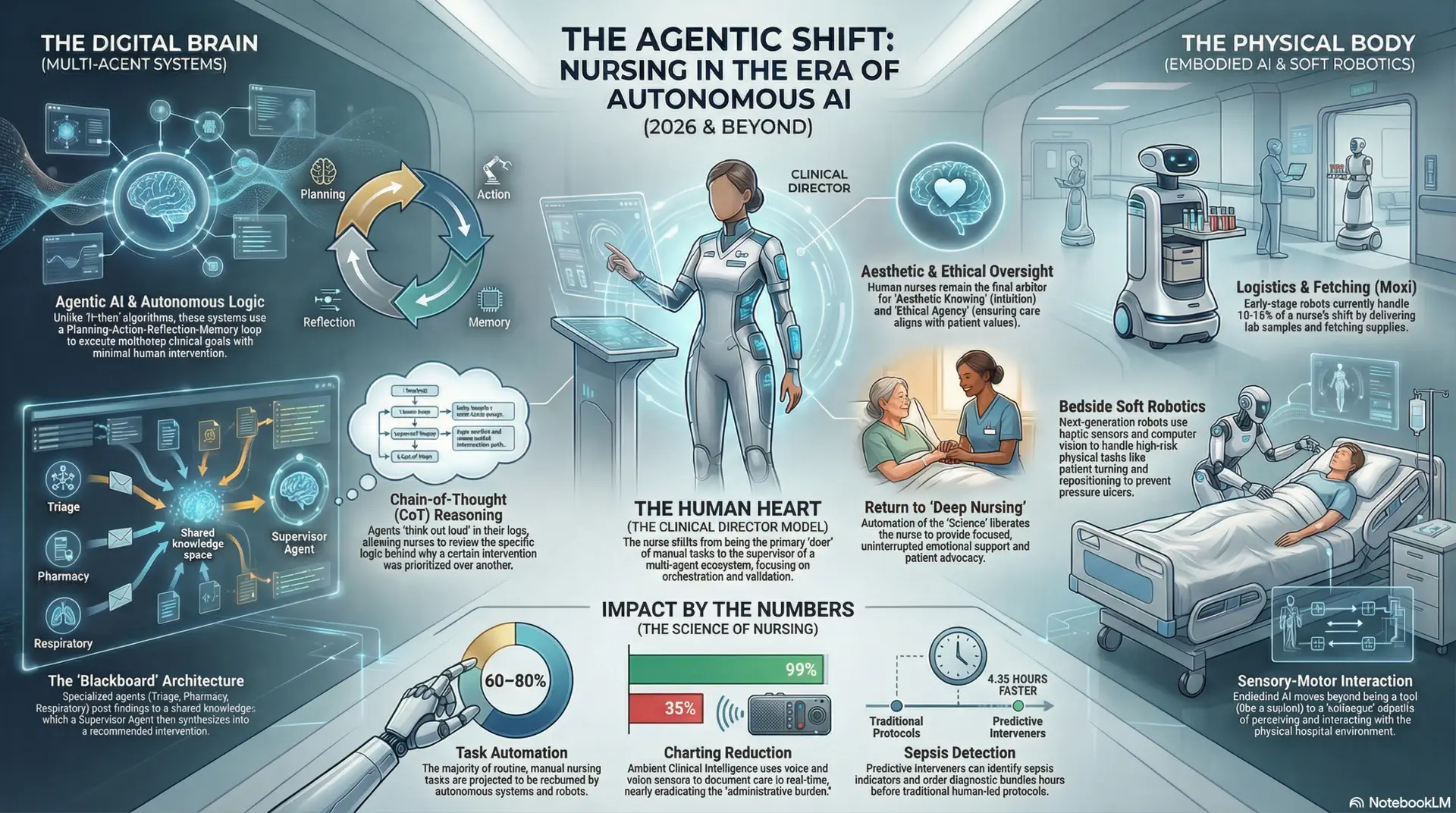

The integration of robotics into clinical practice has historically been defined by tele-operation, where a human surgeon directs a machine, such as the Da Vinci Surgical System, from a remote console. However, the next frontier in healthcare involves “Embodied AI”—autonomous agents that possess a physical presence and the cognitive capacity to perform tasks without constant human steering (Morale, 2025). The premise of this exploration is that it is now technically feasible to develop robots that can independently assess, debride, and dress wounds.

The impetus for this shift is largely economic and demographic. Chronic wounds affect millions of individuals globally, and studies indicate that frequent, consistent debridement—the removal of dead or infected tissue—can significantly accelerate healing rates (Chadwick et al., 2025). When wound care is performed autonomously, the frequency of intervention can increase from weekly to daily, dramatically reducing the risk of opportunistic infections and potential amputation. While current AI is excellent at “seeing” (diagnostics) and current robotics are excellent at “moving” (surgery), the convergence of these two fields into a single, embodied agent is what will enable autonomous routine care. This synthesis requires a move away from rigid industrial design toward a more biological, adaptive approach to mechanical interaction.

II. Barrier 1: Haptic Intelligence and Tactile Sensitivity

A primary technical barrier to robotic wound care is the “rigid-body problem.” Traditional industrial robots are constructed from rigid metals and plastics, which lack the compliance and tactile feedback required to interact with delicate human skin. Human skin varies significantly in elasticity and hydration; a robot must be able to distinguish between a firm scab, healthy granulated tissue, and soft, necrotic slough (Yin et al., 2025). Without this sensitivity, a machine might accidentally apply excessive force to an area of venous insufficiency, leading to further tissue breakdown.

To overcome this, researchers are turning to Soft Robotics. By using hydrogel-based actuators and pneumatic “muscles,” robots can achieve a “tissue-matched modulus”—a state where the robot is as soft as the material it is touching (Yap et al., 2023). Furthermore, the implementation of “Electronic Skin” (E-Skin) provides the AI with high-resolution feedback. These sensors can detect micro-forces at the milligram level, allowing the robot to perform “digital palpation.” By measuring the resistance and rebound of the skin, the robot can identify underlying edema or abscesses that might not be visible to the eye. This allows the AI to apply precisely the amount of pressure needed to cleanse a wound without triggering a pain response or damaging fragile newly-formed capillary beds.

III. Barrier 2: Multi-Modal Computer Vision and Diagnostic Accuracy

Wounds are complex, three-dimensional structures that often hide clinical information beneath the surface. Standard 2D RGB cameras used in early diagnostic tools are insufficient for autonomous care because they cannot assess wound depth or perfusion (blood flow). For instance, a wound may look healthy on the surface but suffer from deep tunneling or undermining that leads to internal infection.

The solution lies in Hyperspectral and Multi-spectral Imaging. These systems allow an embodied AI to “see” light frequencies beyond human vision, identifying oxygen saturation levels and even specific bacterial colonies, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, before they become visible to a nurse (Thatcher et al., 2023). By integrating LiDAR and structured light, robots can create millimetric 3D point cloud maps of the wound topology. This data allows the robot to monitor healing progress with 95% accuracy, detecting subtle changes in volume that indicate whether a treatment is working. Beyond assessment, this mapping enables the robot to autonomously 3D-print or custom-cut dressings that fit the wound’s exact shape on a daily basis (Keseraju, 2024). This level of precision ensures that the dressing covers only the wound bed, protecting the surrounding periwound skin from maceration caused by excess moisture.

IV. Barrier 3: Manipulation in Unstructured Environments

Unlike a factory floor, a hospital room or a patient’s home is an “unstructured environment.” Patients are dynamic; they flinch, breathe, and shift positions during treatment. For a robot to perform a task as precise as debridement—the mechanical removal of biofilm—it must compensate for this movement in real-time. Even a minor flinch during a cleaning procedure could lead to a laceration if the robot operates on a fixed coordinate system.

Recent breakthroughs in Active Motion Compensation use high-speed tracking to “sync” the robotic arm’s movements with the patient’s breathing or involuntary tremors (Brattain et al., 2025). Furthermore, “Sim-to-Real” transfer allows AI models to be trained in physics-based simulators that replicate billions of human movement scenarios, ranging from an elderly patient’s shaky hand to a sudden cough. This ensures that if a patient suddenly moves, the robot can use edge computing—processing data locally at the site of care—to pivot or stop its activity in milliseconds. This reaction time is significantly faster than that of a human clinician, providing a safety buffer that makes autonomous physical intervention viable even in home-care settings where supervision is minimal.

V. Barrier 4: Clinical Integrity and the “Sterility Logic”

Robots are complex mechanical systems with joints and crevices that can harbor pathogens, posing a high risk of cross-contamination in a clinical setting. Standard sterilization methods, such as autoclaving, would destroy sensitive electronic components like CMOS sensors and lithium-polymer batteries. Consequently, the robot itself could become a vector for hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) if not managed correctly.

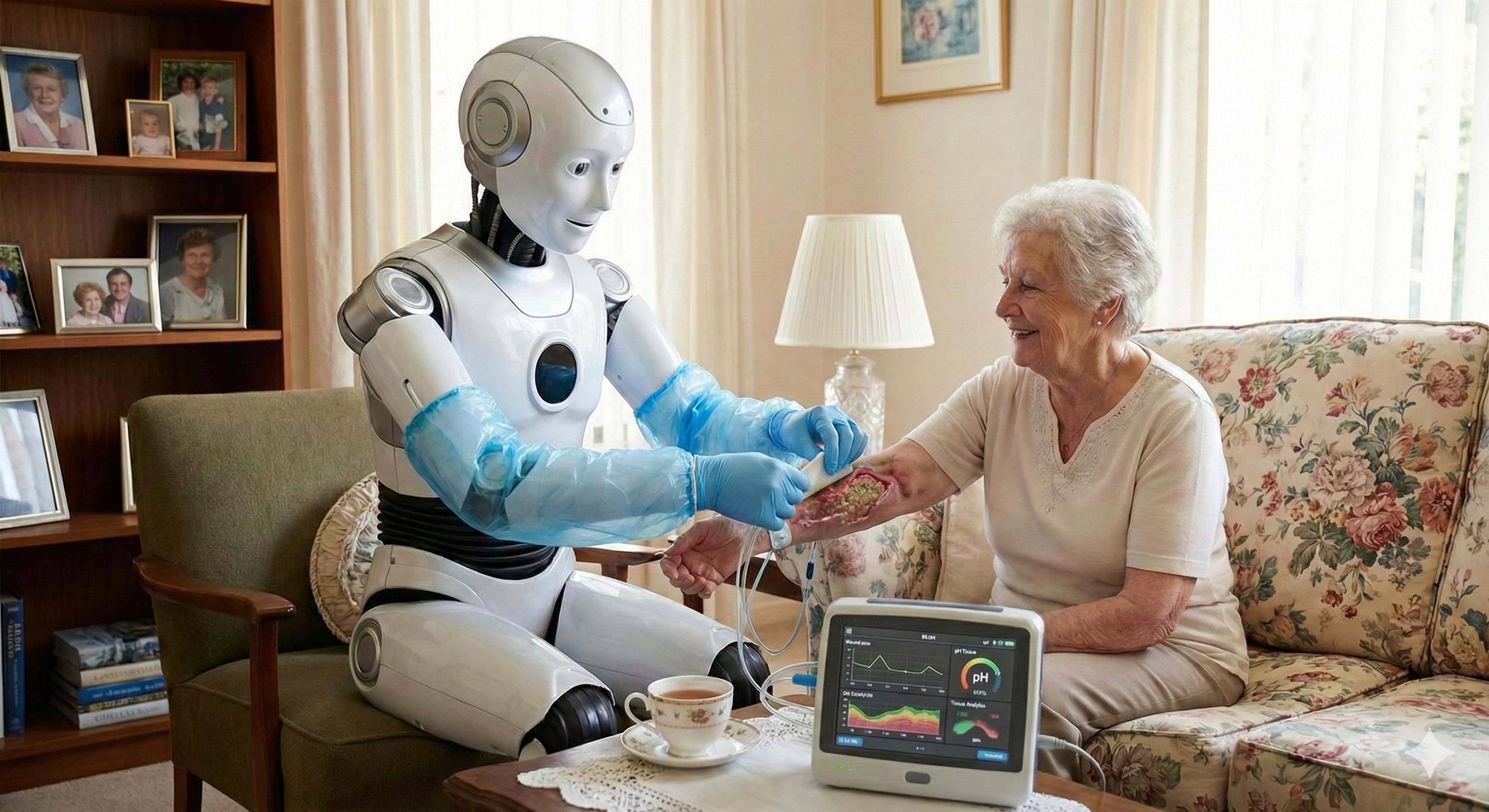

Overcoming this barrier requires a multi-faceted approach to “Sterility Logic.” First, robots are being designed with self-sterilizing materials, such as copper-infused polymers or antimicrobial coatings that naturally kill 99.9% of bacteria upon contact (Roels et al., 2025). Second, the use of modular, single-use “sleeving” allows the robot’s main body to remain protected while a biodegradable, sterile skin is replaced between every patient encounter. This acts as a robotic equivalent to a nurse’s sterile gloves. Finally, integrated UV-C disinfection lamps can be used by the robot to “zap” its own end-effectors and the surrounding workspace after a task is completed (MetraLabs, 2025). This autonomous cleaning cycle ensures that the machine is perpetually ready for the next patient without human intervention, maintaining a level of clinical integrity that meets stringent surgical standards.

VI. Barrier 5: Trust, Liability, and the Human Interface

The final and perhaps most significant barrier is not technological, but psychological and legal. Patients often report anxiety regarding the “cold” or “mechanical” nature of robotic care, especially when the care involves an open, painful wound. Legally, the transition from human error (medical malpractice) to machine error (product liability) remains a complex regulatory hurdle that could delay the adoption of autonomous systems.

To build trust, embodied AI is adopting principles of Social Robotics. This involves more than just a screen; it includes natural language processing that allows the robot to explain each step of the wound care process to the patient in a soothing, informative tone. By verbalizing its intent—e.g., “I am now going to apply a cooling saline wash”—the robot reduces the patient’s “startle response.” In the near term, a “Doctor-in-the-Loop” model will likely prevail, where the robot performs the physical labor under the remote supervision of a human specialist (Inrobics, 2025). This allows for a gradual transition where the AI’s autonomous decisions are validated by human expertise. Over time, as datasets prove that robotic consistency leads to better outcomes and fewer complications, the legal framework will likely shift to accommodate autonomous medical agents as standard-of-care tools.

VII. Conclusion: The Rise of the Specialist Robot

The evolution of autonomous wound care is an inevitable consequence of the “Embodied AI” maturation. As soft robotics, multi-spectral imaging, and motion compensation algorithms continue to advance, specialized robotic units will move from the laboratory to the bedside. The end state of this journey is the availability of autonomous home-care units that provide “micro-care”—performing daily dressing changes and cleanings that would be logistically and financially impossible for a human nursing staff to conduct. These machines will act as persistent guardians, catching the earliest signs of infection through constant monitoring.

Crucially, this technology is not intended to replace the nurse. Instead, it serves as a vital clinical adjunct. By offloading the highly repetitive, physically demanding, and data-heavy tasks of routine wound dressing, embodied AI empowers nurses to operate at the top of their license. The machine ensures the technical precision of the bandage and the sterility of the environment, while the nurse provides the complex empathy, holistic patient assessment, and strategic oversight that define high-quality human care. The partnership between the embodied AI and the nurse represents a new era of healthcare—one where precision engineering and human compassion work in tandem to solve the most persistent challenges in modern medicine.

References

Brattain, S., et al. (2025). AI-GUIDE: Autonomous needle insertion and tracking in unstructured medical environments. Proceedings of the IEEE.

Chadwick, P., et al. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in wound care: applications, evidence and future directions. Wounds International, 16(3).

Inrobics (2025). Ethical challenges of robotics in healthcare: Autonomy, Responsibility, and Human Supervision. Journal of Healthcare Ethics.

Keseraju, V. (2024). Hybrid AI-driven approach for wound assessment: Integrating VGG16 CNN and GPT-3.5 for diagnostic precision. Clinical Informatics Journal.

MetraLabs (2025). STERYBOT®: UV-C disinfection robot and clinical integration studies. MetraLabs GmbH.

Morale, C. G. (2025). Embodied Artificial Intelligence for Emergency Care in Unstructured Environments. Carnegie Mellon University Robotics Institute.

Roels, E., et al. (2025). Self-healing materials for soft robotics: An overview of the state-of-the-art. Advanced Materials.

Thatcher, J. E., et al. (2023). Multispectral imaging and voting ensemble deep convolutional networks for non-healing burn identification. Journal of Burn Care & Research.

Yap, H. K., et al. (2023). A review on self-healing featured soft robotics. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 10.

Yin, S., et al. (2025). Advancing soft, tactile, and haptic technologies: recent developments for healthcare applications. Frontiers in Robotics and AI.